In my practice, hundreds of parents have asked me about raising children in a way that supports their emotional health. I’m always working to help break down how we talk about feelings with our children and respond to them in our everyday lives. This week, I was lucky enough to sit down with Dr. Marc Brackett, Founding Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and author of Permission to Feel.

Here are the key take-aways I learned.

(if you missed the episode or haven’t listened to it yet, check it out, here.)

There are no good or bad feelings. Can we all finally agree on this? As a society, we love to rejoice in everyone’s happiness, satisfaction, fulfillment, pleasure, but then look down on anxiety, worry, fear, loneliness or isolation. For our children, I often see parents so unable to tolerate their child’s distress. They work so hard to “distract” their children into feelings that feel “better.” If we want to raise humans that accept and acknowledge the wide range of feelings in the human experience, we need to start by honoring the principle that all feelings are information, are equal, are important, valid, meaningful and acceptable.

When we grant ourselves the permission to feel, we are not enslaved by our emotions. Instead, we can acknowledge them and work toward finding a way to understand them and work through them. We need not hold them inside - leading to worsening mental and physical health - or work to deny them. If we accept that we all have feelings, that they are present for each one of us, we can make them our visitors instead of our dark secrets.

Like the weather, feelings come and feelings go. Not even the greatest day of sunshine lasts forever. Though any given moment may feel painful, endless, impossible, it eventually gives way to another. I’m reminded of the way we talk about nutrition for young children, when they are struggling with picky eating. We tell parents that it isn’t about one day, or one bad weekend, nutrition is measured over time - over a week or several weeks. One snapshot simply doesn’t tell us the whole picture. Parents are always surprised by this, but it makes sense. We are a culmination of all of our experiences, not just our worst (or best) days.

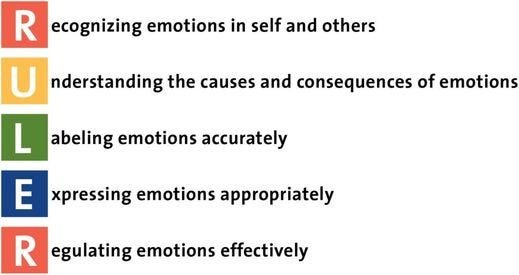

As Dr. Brackett says, we can become a society of emotion scientists. That means we follow the principles of his work, RULER. And we do the hard work ourselves. We don’t separate our own lack of emotional intelligence, of understanding, or of engaging, in order to “do something for our kids.” Instead, we are part of this process, constantly working to help ourselves and our families become more aware of the nuanced and complex world of emotion.

NOTE: This also means, we need to be the role models for our children about our own emotions. Model for them what we experience, not in a way that makes them feel they have to care for us, but in a way that shows them that we have a range of feelings, and healthy ways to cope with them.

If we want our children to have good mental health, positive relationships, personal satisfaction and well-being, we need to invest in these skills every day. So much of my work has focused on prevention - if we can help families early, we can prevent concerns later - and this is no different. So many of us (and as a society) ignore mental health until there is a diagnosis. Instead, let’s invest our time and energy talking about mental health, about emotions, empathy, perspective taking, and regulation. How to handle disappointment, failure, setbacks, or hardship, and how to manage our relationships. Let’s do the work from the start.

My own “aha” moment.

Clearly I am BIG on feelings. I’m all in. I get eye rolls from my daughters with my constant refrain, “all feelings are welcome, all behaviors are not.” Yet even I had not realized the potential misleading message of a “thinking brain” if the implication is that it is absent of feeling. It is well established that we are learning from our feelings, that feelings are giving us information about what we need. Learning about our temperament, how we respond to the world, how we like (and don’t like) to be treated, what we care about, who we want to be, what excites (and terrifies) us, and on, and on, and on. So if we are learning from these feelings…we have to respect that they are a big part of our thinking and listen to them. Of course it does not mean we listen to them and act on all of them, but we do need to know what they are telling us, and be able to determine what actions to take. This is why during this episode I thought about one of my favorite and very well known metaphors on self regulation - using your wizard vs lizard brain.When we talk about teaching our children to use their wizard brain and not there lizard brain, does that inadvertently send the wrong message about feelings? Does it suggest the “lizard” or feelings part of the brain is inherently not smart?The feelings are in fact quite smart, they just sometimes might need a dose of a different type of smart to make choices that serve us. It turns out that that lizard state is actually communicating a LOT - even if we’d rather change the channel. So, as a result of this “aha” moment, I’m rethinking the “get back into your wizard brain” metaphor that I’ve been using.

I hope you enjoyed this article - and I hope you’ll be back for more.

With gratitude,

I wish I had a better metaphor for how emotions and thinking interact. But I very much appreciate that you are rethinking the standard split between them. More than the "Blank Slate" I think this split is the worst idea in psychology. Perhaps some sort of balance metaphor would work. A dancer or gymnast? There is also a dark side to reason when it distances us from the harm we do to others.