Thanks for reading Raising Good Humans on Substack! My first book, The Five Principles of Parenting: Your Essential Guide to Raising Good Humans is now available for purchase here.

In the quest for effective strategies to support our kids' mental well-being, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a powerful, evidence-based approach. Though CBT is not a shiny, new intervention, the core principles and tools of CBT can be incredibly valuable for everyday parenting, fostering resilience and healthy coping mechanisms. This week I asked Dr. David Anderson, Vice-President of Public Engagement and Education, and Senior Psychologist at the Child Mind Institute to talk about CBT on the Raising Good Humans Podcast.

This episode isn't about diagnosing or treating clinical conditions yourself, but rather understanding foundational CBT concepts and translating them into practical, accessible techniques for your family. Think of it as equipping your child (and yourself!) with a robust mental wellness toolkit.

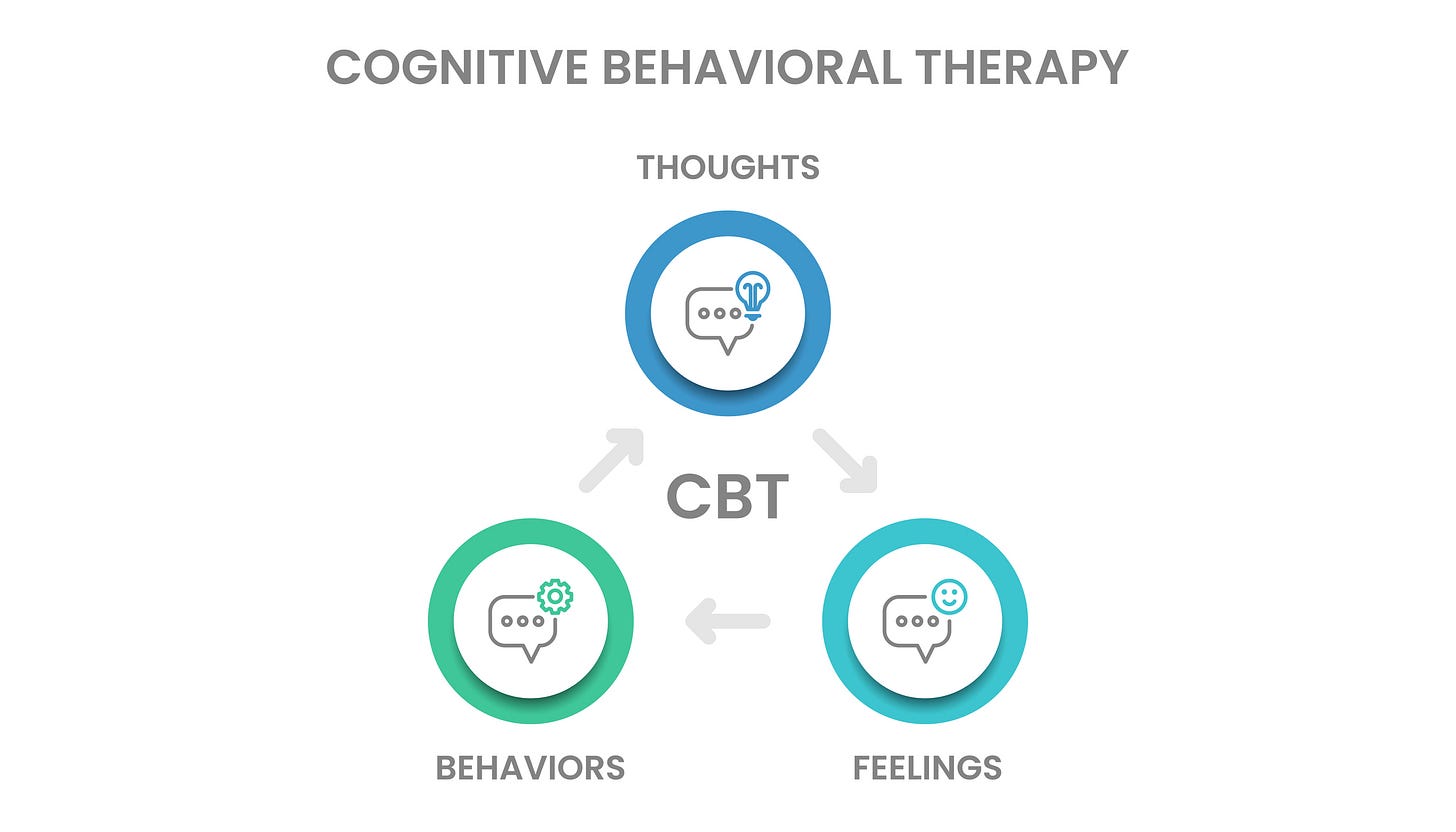

What exactly is CBT? At its heart, CBT illuminates the interconnectedness of our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, known as the “cognitive behavioral triangle.”

Cognitive (Thoughts) = These are our internal monologues, beliefs, interpretations, and assumptions about ourselves, others, and the world.

Emotions = How we feel – sadness, joy, anger, anxiety, excitement, etc.

Behaviors = The actions we take, or don’t take, in response to our thoughts and feelings.

CBT teaches us that by understanding, and, at times, consciously shifting our thoughts or behaviors, we can influence our emotional state. This isn't about denying feelings, but about gaining agency over how we respond to them.

For our children, this understanding needs to be concrete and experiential, not theoretical. As Dr. Anderson explains, this is a toolkit we are providing, not a lecture we are forcing them to endure.

Here are three practical areas of CBT that parents can integrate into daily family life, helping children (and adults!) build essential self-awareness and coping skills:

1. Emotion Monitoring

The first crucial step in any self-awareness journey is simply tuning into our feelings and their intensity. Many of us, both kids and adults, are out of touch with our emotional experience until it becomes overwhelming. Bringing attention to our children’s fluctuating emotions also highlights their temporary nature, reminding us that feelings come and feelings go.

How to use it at home:

Create an "Emotion Log." This doesn't have to be a rigid, clinical document. For younger kids, it might be a simple chart with emojis or colors where they can point to how they feel. For older kids and teens, it could be a notes app on their phone or a journal. The goal is to track:

The emotion: What are they feeling? (Go beyond "good" or "bad." Use an emotion wheel to expand vocabulary: "frustrated," "lonely," "excited," "proud," "calm," "overwhelmed.")

The situation: What was happening right before or during the feeling?

Intensity: On a scale of 1-10, how strong was the feeling?

Casual check-ins. Instead of a formal log, simply ask open-ended questions throughout the day: "How was that soccer practice for you today? What emotions came up?" or "I noticed you seemed frustrated with your homework. What was that feeling like on a scale of 1-10?"

Model it yourself. Share your own emotions and their intensity. "I felt a little stressed (7 out of 10) when I had to finish that work before dinner." This normalizes emotion and shows them you're doing the work too.

2. Behavioral Activation and Activity Scheduling

Behavioral activation is about intentionally scheduling activities that provide mood bursts, whether your child is feeling down or not. It’s about proactively "emptying your bucket" of stress before it overflows, and tapping into activities that have supported your child before.

How to use it at home:

Identify mood boosters. Ask your child, "What activities make you feel good, even a little bit?" This could be anything from playing outside, listening to a specific song, drawing, reading, calling a friend, or watching a favorite show. For parents, it might be a walk, listening to music, or reading.

Schedule "Wellness Habits." Work with your child to ensure basic wellness habits are in place, regular movement, eating, hydration, and sleep. You can never overstate the importance of these “basics” in overall mood!

Make a habit. Encourage scheduled activities even when your child isn't overtly stressed. "Let's go for our walk before dinner, even though you've had a good day. It's a nice way to clear our heads." This builds a buffer against future stressors.

Create a “Sensory Toolkit.” When things do get tough and a feeling is overwhelming, help your child identify sensory inputs that can soothe or distract. This is about "riding the wave" of intense emotion when you can't change the situation.

What do you like to look at? (e.g. A favorite picture, nature, a funny video)

What do you like to listen to? (e.g. Music, a calming sound, an engaging podcast)

What do you like to taste? (e.g. A piece of candy, a cup of coffee)

What do you like to feel? (e.g. A cozy blanket, a fidget toy, squeezing ice)

What do you like to smell? (A favorite scent, a baked treat)

Kids often do this naturally (cranking up music when upset), so validate these healthy coping mechanisms.

3. Cognitive Restructuring

We can all get stuck in “thinking traps” where we automatically interpret situations in biased or unhelpful ways. These mental shortcuts can cause us to jump to conclusions or magnify negative aspects of reality. The goal in CBT is to gain distance from unhelpful thought patterns, and cultivate more balanced, realistic perspectives. It empowers children to challenge self-defeating narratives, reduces rumination, and fosters a growth mindset.

How to use it at home:

Identify negative thoughts. When your child is upset, gently ask about their thoughts. For example, if they get a bad grade: "What thoughts are going through your head about this?"

Do an "Evidence Check.” Once a thought is identified (for example, "I suck at math"), introduce the idea of gently questioning it. Ask:

"What evidence do you have that this thought is 100% true?"

"What evidence do you have that this thought isn't 100% true, or that there's another way to see it?"

"Is there another way to think about this situation?"

Bring perspective. Help your child differentiate between a temporary situation and a permanent characteristic. "You're struggling with this math problem right now, not that you'll always be bad at math."

Support problem solving. Once thoughts are reframed, shift to what can be done. Can your child make a plan to study differently? To make amends to a friend? To support someone else outside of themselves?

Underlying all these CBT tools is one of my favorite tools of all: the pause. Whether it’s a pause to identify an emotion, to engage in a mood-boosting activity, or to challenge a "thinking trap," the pause is your superpower. It creates space between a stimulus (a challenging situation, an intense emotion, a negative thought) and your response, allowing for conscious choice rather than automatic reaction. Teaching your child the power of the pause, and modeling it yourself, is perhaps the most fundamental "practical tool" you can offer from the CBT framework. It's the gateway to applying all other skills effectively.

A quick reminder to buy my first book, The Five Principles of Parenting, and write a review from wherever you order. Reviews really help to get the book noticed, and to spread the word. Please especially rate and review any books purchased on Amazon (it shockingly really, really matters!). Also, when you receive the book, snap a quick pic with it and post on social media. Share one thing you love about it and help me to get more copies into the hands of parents in your community. Tell a friend about the book, or about something you found helpful in the book. Parents look to each other for advice, and I’d love to be a part of the support you pass on to your loved ones.

Sometimes I try to voice my feelings with the phrase “I’m losing my patience”, I don’t think that’s the same as what you suggested about stating your emotions. Any recommendations on this phrasing specifically?